- cross-posted to:

- [email protected]

- cross-posted to:

- [email protected]

cross-posted from: https://lemmy.world/post/11477056

Owls have special anatomical structures that let them twist their heads all over the place, but the current consensus is the rotational limit is 270 degrees. They have twice the number of cervical vertebrae we have, and they are coiled like a spring to aid rotation, while special channels help prevent pinching off nerves or blood flow.

There are 2 reasons owls move their heads all over. The most important is that their eyes can only face straight ahead. They’re shaped like light bulbs, with the big end on the inside of their skull, so they can’t look at anything without moving their whole head.

Secondly, most of hear in 3 dimensions, and their face shape helps them hear. When you live in the dark, hearing can at times be more important than vision. The concave shape of the owl’s face funnels sound to their ears, working the same as you cupping your hands around your ears does. So all that head bobbing and twisting is them looking at something analytically with their eye vision and “ear vision.”

I’m a little curious if they can twist further, but I don’t know if it’s practical. If they overextend one way, they have to snap back around extra far to track whatever they’re looking at as it passes outside the range of vision that direction, making them take their eyes off their target longer.

Here is a writeup of the study by New Scientist

Owls should be able to rotate their heads a full 360 degrees, according to an analysis of the birds’ skeletons and muscles – but some researchers still have their doubts.

It has long been known that owls have extremely mobile necks. The birds have been recorded turning their heads entirely upside down, for instance, or rotating them through 270 degrees while keeping their bodies stationary. But Aleksandra Panyutina at Tel Aviv University in Israel and her colleague Alexander Kuznetsov, an independent researcher, suspect an owl’s neck is more flexible still.

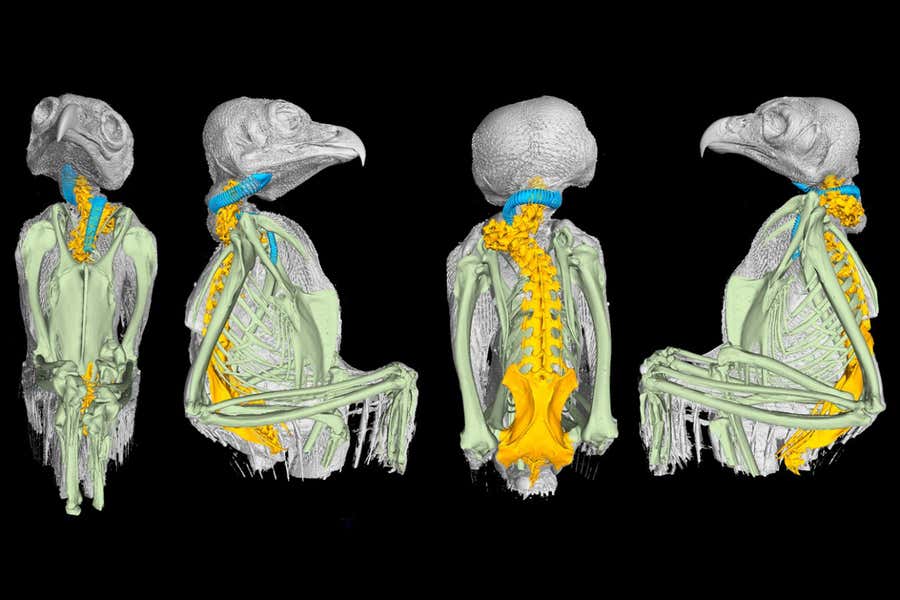

The two researchers obtained the bodies of eight deceased owls – belonging to a total of five different species – from two academic institutes in Russia. They then took CT scans of each bird as they rotated its head.

This revealed that owls rely on two strategies during a head turn. First, they rotate some of the joints between the bones in their neck, which allows them to turn their heads up to 126 degrees. Secondly, they physically twist their spine, giving it a spiral staircase-like appearance. Although this coiling severely contorts the spine, Panyutina and Kuznetsov discovered the motion doesn’t damage the bones, ligaments or muscles in the owl’s neck – even if the head turns in a full circle.

As such, Panyutina is confident that “live owls can perform a 360-degree turn”.

Michael Habib at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, who has researched some of the adaptations that allow owls to perform extreme head turns, says the new study is “very cool”. But he doesn’t think we will ever see an owl’s head rotate completely around.

“They were asking whether there’s anything in the bone and muscle that would necessarily prevent a 360-degree turn, and they found that the answer is, somewhat surprisingly, no,” says Habib. But he thinks other anatomical features will probably forbid such turns. Critically, Habib says, the nerves running up the neck would be damaged during a 360-degree spin, potentially leaving an owl unable to fly for several days while the nerves healed. “Nerves don’t like being stretched,” he says.

However, Panyutina disagrees this would be a problem, particularly for nerves, such as the vagus nerve, that pass over the top of the neck muscles. Their placement means these nerves wouldn’t stretch as the bones beneath the muscles twisted and contorted. “The vagus runs freely over the muscles and so easily finds a shorter way during extreme turns,” she says.

To settle the matter, researchers may have to perform experiments with living owls. Panyutina proposes training the birds to focus on a specific target, and then placing them on a rotating platform to see whether they can retain focus on the target through a 360-degree turn.

Mouais, toujours se méfier quand c’est pas vu en vrai, les simulations c’est bien mais y’a rien de mieux que l’observation directe du phénomène, surtout en bio !