capital like “no fair, do over, i wasn’t ready!”

getting work done, hopefully the third referendum for building up a comission that can organise the fourth referendum that can pressure parliament into recognising the “affordable access to accessible affordability act” that can then pave the way into not holding the fifth referendum because really, that’s just playing into the AfD’s hands at that point, maybe later kiddo

Holding a warm up referendum to determine whether private companies be allowed to own more than 3000 residential properties. I’m surprised near about 40% voted against it. But seeing how Brexit went I’m guessing the real estate companies were given free reign to spread lies.

Holy fuck that’s such a high limit.

Oppose: SPD (German SocDem party)

Name a more iconic duo than “SPD” and “betraying leftism to collaborate with capital”

Ah, the Red and Black flag…

Average centrist pundit:

We tried it before and it didn’t work. Why would we vote for it again?

“the crimean annexation resolution was fake because they did it a bunch!”

also liberals:

So 12 companies control 243,000 units, or about 20k units each.

Wouldn’t they just split into 7 individual firms each?

I have a better idea: We split the people owning the companies into 7 pieces each.

Only by having a few companies, can the efficiencies of scale be used to extract profit.

The legal structure of a firm doesn’t usually impact it’s actual operations.

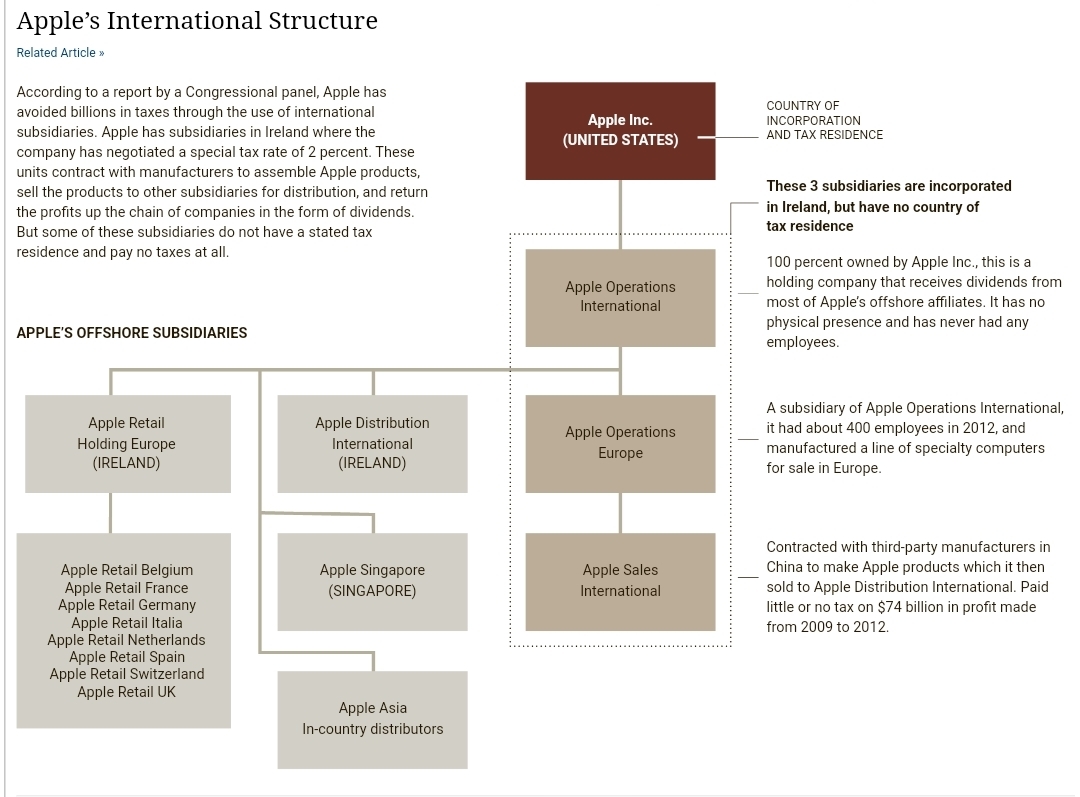

For example, Apple’s actual web of firms is significantly more complex but here’s a simplified overview:

In this case, you might expect the rental firm to spin out it’s functions as a property management and maintenance firm and charge the new smaller holding firms a percentage fee - with no change in actual underlying ownership.

It is true that a company can be broken up into different pieces or verticals for different reasons, but the key is that they do not act like an internal market where profit is extracted from each interaction with one another. For the most part they are allocated a set of resources and charged with delivering whatever they are responsible for, and then every year they are re-budgeted to achieve the same results or better, ideally at the same cost or less. Savings are transferred out and eventually to the shareholders.

So, what I am saying is that instead of having lots of different companies extracting profit from one another at each part in the system, creating inefficiencies, a large company can basically dictate down what everything costs and wherever excess value can be extracted, it is done more efficiently, captured more completely and transferred upwards towards a single set of shareholders.

Basically a corporation is a perfect command economy

On your point about internal competition too:

But the consensus among the business press and dozens of very bitter former executives is that the overriding cause of Sears’s malaise is the disastrous decision by the company’s chairman and CEO, Edward Lampert, to disaggregate the company’s different divisions into competing units: to create an internal market

Lampert, libertarian and fan of the laissez-faire egotism of Russian American novelist Ayn Rand, had made his way from working in warehouses as a teenager, via a spell with Goldman Sachs, to managing a $15 billion hedge fund by the age of 41. The wunderkind was hailed as the Steve Jobs of the investment world. In 2003, the fund he managed, ESL Investments, took over the bankrupt discount retail chain Kmart (launched the same year as Walmart). A year later, he parlayed this into a $12 billion buyout of a stagnating (but by no means troubled) Sears.

At first, the familiar strategy of merciless, life-destroying post-acquisition cost cutting and layoffs did manage to turn around the fortunes of the merged Kmart-Sears, now operating as Sears Holdings. But Lampert’s big wheeze went well beyond the usual corporate raider tales of asset stripping, consolidation and chopping-block use of operations as a vehicle to generate cash for investments elsewhere. Lampert intended to use Sears as a grand free market experiment to show that the invisible hand would outperform the central planning typical of any firm.

He radically restructured operations, splitting the company into thirty, and later forty, different units that were to compete against each other. Instead of cooperating, as in a normal firm, divisions such as apparel, tools, appliances, human resources, IT and branding were now in essence to operate as autonomous businesses, each with their own president, board of directors, chief marketing officer and statement of profit or loss. An eye-popping 2013 series of interviews by Bloomberg Businessweek investigative journalist Mina Kimes with some forty former executives described Lampert’s Randian calculus: “If the company’s leaders were told to act selfishly, he argued, they would run their divisions in a rational manner, boosting overall performance.”

And so if the apparel division wanted to use the services of IT or human resources, they had to sign contracts with them, or alternately to use outside contractors if it would improve the financial performance of the unit—regardless of whether it would improve the performance of the company as a whole. Kimes tells the story of how Sears’s widely trusted appliance brand, Kenmore, was divided between the appliance division and the branding division. The former had to pay fees to the latter for any transaction. But selling non-Sears-branded appliances was more profitable to the appliances division, so they began to offer more prominent in-store placement to rivals of Kenmore products, undermining overall profitability. Its in-house tool brand, Craftsman—so ubiquitous an American trademark that it plays a pivotal role in a Neal Stephenson science fiction bestseller, Seveneves, 5,000 years in the future—refused to pay extra royalties to the in-house battery brand DieHard, so they went with an external provider, again indifferent to what this meant for the company’s bottom line as a whole.

Executives would attach screen protectors to their laptops at meetings to prevent their colleagues from finding out what they were up to. Units would scrap over floor and shelf space for their products. Screaming matches between the chief marketing officers of the different divisions were common at meetings intended to agree on the content of the crucial weekly circular advertising specials. They would fight over key positioning, aiming to optimize their own unit’s profits, even at another unit’s expense, sometimes with grimly hilarious result. Kimes describes screwdrivers being advertised next to lingerie, and how the sporting goods division succeeded in getting the Doodle Bug mini-bike for young boys placed on the cover of the Mothers’ Day edition of the circular. As for different divisions swallowing lower profits, or losses, on discounted goods in order to attract customers for other items, forget about it. One executive quoted in the Bloomberg investigation described the situation as “dysfunctionality at the highest level.”

As profits collapsed, the divisions grew increasingly vicious toward each other, scrapping over what cash reserves remained. Squeezing profits still further was the duplication in labor, particularly with an increasingly top-heavy repetition of executive function by the now-competing units, which no longer had an interest in sharing costs for shared operations. With no company-wide interest in maintaining store infrastructure, something instead viewed as an externally imposed cost by each division, Sears’s capital expenditure dwindled to less than 1 percent of revenue, a proportion much lower than that of most other retailers.

Yup I was absolutely thinking of Lampert. I was also thinking of a department that I deal with personally that is run like that and they are a bunch of fucking assholes.

I don’t think we are disagreeing, my point is that these housing companies can continue to operate as a single large company even if they are legally a set of different firms - like the example of Apple.

You can address this by crafting general antiavoidance laws but at least in tax there’s rarely any desire from the state to prosecute.

Oh yes, agree completely

:vote:

:vote: