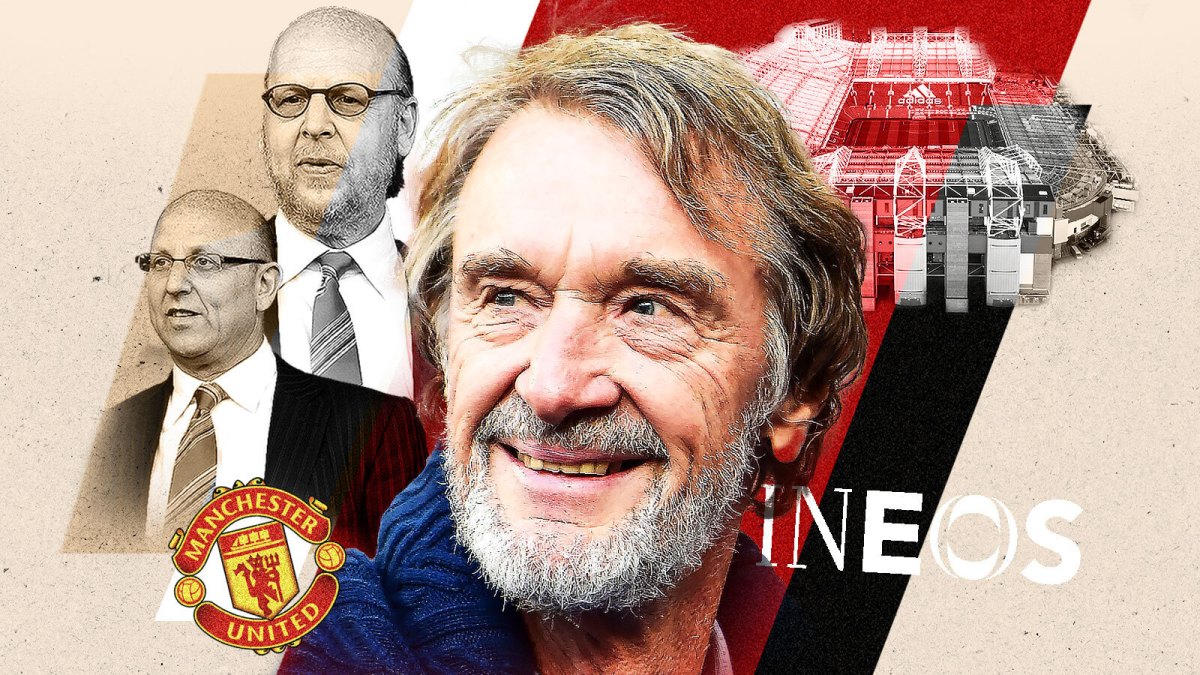

What do you give the multi-billionaire who can have it all — or 25 per cent of Manchester United for starters? For Sir Jim Ratcliffe’s 70th birthday, colleagues pulled together a video of goodwill messages from stars including David Beckham, Sir Alex Ferguson and Eric Cantona.

Ratcliffe was especially delighted by the appearance of Cantona, who was his footballing hero as the galvanising force of the first great Ferguson era. “He had presence. He was the figurehead of Manchester United,” Ratcliffe noted of the way the France forward led the club into a new period of dominance after 26 years without a league title.

Now United are in another drought — it has been more than a decade since they were domestic champions, never mind conquerors of Europe. Manchester City travel to Old Trafford on Sunday as Treble winners and leaders in all the key sporting criteria from first XI to manager, recruitment to academy. United look for a new figurehead, someone to drag them from mediocrity and, this time, hopes fall on Ratcliffe himself.

Even for one of Britain’s richest men, who is used to signing off deals for far greater amounts than £1.3 billion for a quarter of a football club, buying a stake in United will represent a landmark deal given the club’s global renown.

One heck of a responsibility too, given the expectations from the club’s hundreds of millions of fans that a new era of ownership is needed to propel United back to the top — an expectancy that comes with many additional questions given the proposal for Ineos to run the football business in a model of co-control, in the short to medium term, with the loathed Glazers.

Ten years after the retirement of Ferguson, United remain a wounded giant, stifled by almost two decades of Glazer ownership. Ratcliffe believes that he and his team can make a difference but it will take time, energy, and resourcefulness. It requires an overhaul of senior staff and culture, an expensive upgrade of the stadium and a belated prioritising of world-class performance.

It is a mighty challenge so it is worth asking; why take it on? “Isn’t a season ticket enough?” Graeme Souness, the former Liverpool great, asked Ratcliffe when news broke that he was looking to buy an English club. But Ratcliffe did not become one of the richest men in Britain, with a fortune estimated at nearly £30 billion by The Sunday Times Rich List, through half measures.

“One should, if one can, try to maximise the number of days that are unforgettable,” the petrochemicals billionaire once noted. Spending some of his billions on United, Ratcliffe’s boyhood club, is like strapping himself into an emotional rollercoaster.

Sport has been a lifelong outlet for Ratcliffe’s competitive nature. Football was his first love and has been in his blood since he was growing up in terraced housing in Failsworth, a former mill town up the Oldham Road on the northeast side of Manchester.

He says that he would look out at the huge red-brick mills against the Lancashire skyline. This was the late 1950s when the city was famous for industrialism and United run so inspirationally by Matt Busby.

Ratcliffe was one of those won over, taken to watch United by his father, who ran a factory making laboratory equipment. The family moved to Hull when he was nine but there would still be trips to big matches. For one away game at Elland Road, a ticketless Ratcliffe had to clamber over a wall to join the throng.

A love of thrill-seeking has led Ratcliffe to embark on polar treks and scale mountains but nothing lifted his pulse like watching United’s extraordinary comeback in the Nou Camp in 1999 to win the Champions League final and clinch the Treble. “Those three minutes are three minutes you never forget in your lifetime, taken from this miserable place to this high that you can’t describe. I have never been kissed by so many grown men in my life,” he said.

Ineos’s investment in cycling, sailing, football, Formula One and other sports has come with wonderful perks and more of those unforgettable days, such as cycling around Monaco alongside Geraint Thomas, sailing with Sir Ben Ainslie, and sitting on the Nice team bus heading to a big match against Paris Saint-Germain.

As talks continue to thrash out a deal to be taken to the United board, the opportunity to buy a stake is, in part, a passion project — at 71, coming full circle in a life that began just down the road gripped by the sporting glory of United. But it would be wrong to mistake this purely for fun. There is a hard-nosed business rationale behind it, too.

Interviewing Ratcliffe four years ago soon after Ineos had bought Nice in the French top division, he was adamant that he would not be the “dumb money” throwing unprecedented billions to buy a big English club. He had baulked then at a £3 billion valuation of Chelsea.

“You quickly get into some pretty stratospheric numbers,” he said. “You can say it’s worth three, four billion but no one has ever paid those sums.”

Now he hopes to secure a phased takeover of United at a world-record valuation for a sporting enterprise, considerably beyond the $4.65 billion (approximately £3.8 billion) paid in 2022 for the Denver Broncos by Walmart heirs, given that negotiations have valued United at more than £5 billion.

Something changed, in part after a conversation with Khaldoon al-Mubarak. The chairman of Manchester City explained how the City Group of clubs had cost about $1.6 billion to acquire but had more than doubled in value. There had been heavy investment but the assets had grown significantly. Valuations of the biggest English clubs have increased on the back of the continued global growth of the Premier League, especially in the United States.

At such a high price, buying United is hardly risk-free but Ratcliffe, like Todd Boehly at Chelsea, believes that the leading English clubs are not going to lose their global allure anytime soon; that the Premier League will remain the strongest worldwide; that the biggest brands, and none in this country, can match United despite a decade of underachievement. This feeling will only strengthen, especially with expansion in competitions such as the Club World Cup.

There is also a commercial imperative to spread the name of Ineos. Ratcliffe used to say that the firm he established with two friends for £84 million at a single site and, 25 years later, has revenues of about £50 billion across several continents, was the “biggest company in the world you have never heard of”. There is nothing like purchasing a famous sporting institution to make a worldwide splash — to help sell Grenadier cars and other products in China and the US as well as Europe.

“It’s really important for us, as we become more of a customer-facing organisation, to see the brand associated with positive sporting outputs and imagery,” Tom Crotty, the Ineos group director, says in Grit, Rigour & Humour — The Ineos Story published this year.

Ratcliffe cites how Red Bull has built a brand through sport. Of taking a stake in the Mercedes F1 team and painting Ineos on Lewis Hamilton’s car, he says: “So you can spend your money on advertising, or you can do it in a completely different way, which is to invest in sport. If I put money into a Formula One team and in consequence get a lot of publicity, it isn’t money that’s disappeared; it’s money that’s invested. And my investment in Formula One will be worth more in five years’ time. So all that brand exposure won’t have cost me anything.”

The original investment in the local sports club in Lausanne six years ago, after the company moved offices to Switzerland, was to develop goodwill with the community. Ineos now spends about £300 million a year on sport, though that will shift significantly with the proposed United deal. Details remain to be seen, including the financing for stadium reconstruction — and how positive the association is for Ineos depending on success on the pitch.

Ratcliffe was already dreaming big by the time he was at Beverley Grammar School and setting up an industrial society in sixth form. “There’s no question, I definitely had a bit of the entrepreneur in me when I was 17,” he says. “I used to think I would rather like to be a millionaire.”

The first of his family to go to university — chemical engineering at Birmingham — he was soon on his way. After various jobs including in finance in the City, he set up Ineos in 1998 along with two friends, Andy Currie and John Reece, to acquire and turn around undervalued off-casts of corporate giants such as BP and ICI.

A quarter of a century later Ineos has vast global interests across more than 25 countries. Interests range from producing the plastic in Lego to shuttling gas from the US to Europe on 20 ocean-going tankers. Assuming the deal is approved, overseeing transfer policy for Erik ten Hag, the United manager, will be a new responsibility.

There will be part of Ratcliffe that believes United’s operations can only be improved not by throwing money at the problem but by smarter thinking. Ineos has already gathered research that shows how little of United’s transfer spending translates to minutes on the pitch compared with a rival like City. “We don’t like squandering money or we wouldn’t be where we are today. It’s part of our DNA, trying to spend sensibly,” he says.

In football, Ineos has had to learn hard lessons at Nice where there has been turbulence off the field, a couple of false starts in player recruitment and strategy before the latest reboot, which has the team lying second in the French top division, unbeaten after nine matches, with a young squad, coach and executive.

United’s outlay demands a fresh set of eyes. Why has Jadon Sancho’s career nosedived? What was the role envisaged for Mason Mount? Why did the fee for Rasmus Hojlund suddenly leap up to £72 million?

But it is also a fine line between an owner who takes interest, and makes senior staff accountable, and one who interferes. A new director of football will be a vital appointment but there is also expected to be a three-man football committee of Ratcliffe, Sir Dave Brailsford, who is the director of sport for Ineos, and Joel Glazer.

Ineos has a remarkably vertical structure for a company of more than 26,000 employees, with Ratcliffe and his fellow owners holding monthly board meetings with the chief executives of each separate division — whether a sports team or oil refinery — in a federal structure. It ensures quick decisions can be made.

“Even with 1:59 [Eliud Kipchoge’s sub-two-hour marathon], that was a monthly board meeting to decide which way to turn — like do we do it on an airfield in Norfolk or an interesting place like Vienna? It’s that testing of people’s decision-making. Then we let them get on with it,” Ratcliffe says.

Like any fan, Ratcliffe has his own strong feelings about players. “They [United] have been the dumb money, which you see with players like Fred,” as he once told me, so it will be a critical test to recruit the right people and to know when to trust, or challenge, the football experts.

Ratcliffe says that one incentive for bidding has been to keep United in British control, which may be scoffed at by those who think that setting up a low-tax residence in Monaco undermines that argument — but he offered the only alternative to the Middle Eastern land grab of top European clubs and a Qatar bid which promised way more than it could deliver.

Certainly roots matter to Ratcliffe, who embraces the caricature of plain-speaking northerner. “Don’t get too hung up on the woke agenda,” he says, whether answering questions on plastic production (effectively telling people if they stop using it, he will stop manufacturing it) or fracking (blaming an “ignorant minority” for blocking it in the UK) or falling out with Gordon Brown, when he was prime minister, over a tax bill and unapologetically moving Ineos out of Britain.

He talks of old-fashioned virtues — “I worry that some of the younger generation haven’t learned some of the basics of good manners, as we have steadily emasculated school teachers, police and increasingly parents from demonstrating some consequence for poor behaviour” — and worries that the UK is slipping as a global force in business, politics, and beyond.

“Grit, rigour and humour” are the central words on the Ineos “compass” but Ratcliffe may want to add perseverance given the challenges of dealing with the six Glazer siblings, and an agreement that has required personal interventions to evade obstacles over many months. It continues to test patience.

There is an argument that it is mad to buy into a football club at all — never mind for a world-record valuation -– given the strains and expectations, all that scrutiny and no guarantees. Ratcliffe could enjoy his two superyachts, several homes across Europe, his own pub in Knightsbridge as well as a New Forest hotel, a ski club in the French Alps and a salmon fishing area in north Iceland.

But a football club gets into the bones in a way that oil refineries and billion-dollar petrochemical deals never will — and that is what surely makes United the most thrilling, and challenging, acquisition of all.

Highlights:

-

There will be part of Ratcliffe that believes United’s operations can only be improved not by throwing money at the problem but by smarter thinking. Ineos has already gathered research that shows how little of United’s transfer spending translates to minutes on the pitch compared with a rival like City. “We don’t like squandering money or we wouldn’t be where we are today. It’s part of our DNA, trying to spend sensibly,” he says.

-

United’s outlay demands a fresh set of eyes. Why has Jadon Sancho’s career nosedived? What was the role envisaged for Mason Mount? Why did the fee for Rasmus Hojlund suddenly leap up to £72 million?

-

A new director of football will be a vital appointment but there is also expected to be a three-man football committee of Ratcliffe, Sir Dave Brailsford, who is the director of sport for Ineos, and Joel Glazer.

-

Ineos has a remarkably vertical structure for a company of more than 26,000 employees, with Ratcliffe and his fellow owners holding monthly board meetings with the chief executives of each separate division — whether a sports team or oil refinery — in a federal structure. It ensures quick decisions can be made.

-

Like any fan, Ratcliffe has his own strong feelings about players. “They [United] have been the dumb money, which you see with players like Fred,” as he once told me, so it will be a critical test to recruit the right people and to know when to trust, or challenge, the football experts.

Thanks for posting

-